It’s nearing that time again; the nights draw in and the weather grows colder. Can you feel it? It’s time for the tabloids to start spouting their spurious lies again, and this means that the gutter press have had to find another subject for their scaremongering. This time it’s an all too common spider friend that they have in their sights: the house spider. I for one find this absolutely hilarious, as I would struggle to think of a more benign arachnid.

Of course not everyone will be so tickled. House spiders (Tegenaria domestica to the press) unfortunately tick all of the boxes when it comes to people’s problems with spiders. They are large, hairy, prolific and fast. They are also completely harmless! I can understand a little the concern over Steatoda, they look a bit like the infamous Black Widow and can inflict a reasonably painful bite. They are also something that people have only recently started to notice thanks to a recent rapid expansion throughout most of the southern UK, though they don’t seem to have quite made it to the northern reaches. They are an introduced species and therefore their range is not quite nationwide just yet. Tegenaria, on the other hand have been here for much longer; you’ve all seen them and we should all know that they pose us no threat.

Beyond this it is certainly worth mentioning that the press are doing their best to spice things up a bit at least. Whether it’s the obsessed Daily Star, with their nearly constant arachnid-hating, or one of the other tabloids, spiders have once again started to make it back into the news in various ways, normally employing words such as “invading”, “rampaging”, “attacking”, or other such scary terms. Now, as it is that season again I shall bring my efforts to debunking each of these in turn, but this time around I am defending the house spider and the hobo spider that the press currently have their knickers in a twist over.

Let’s start with a few facts. Tegenaria is a genus of spider that is not invasive: in fact it has been introduced to much of the rest of the world from Europe! It consists of around 100 species, of which we enjoy just a few here in the UK. I’m not going to get too deeply involved in differentiating between the myriad subspecies as a: nomenclature and taxonomy of arachnids are headache-inducing at best and are also constantly changing, with Tegenaria currently under revision and some species seem destined for Erategina, so all these scientific names are soon to be redundant anyway. Suffice it to say it can be very difficult to tell spiders apart at times. So if many learned Arachnologists can sometimes struggle with these things – often a conclusive ID can only be obtained with microscopic inspection – how are we supposed to believe that a pest controller or nurse can make a positive identification, often without seeing the actual specimen?

Anyway, back to Tegenaria (or Erategina). Yes, they are the archetypical ‘creepy crawly spider’ that people tend to see as the days get colder. More often than not you will encounter a male out and about looking for a female to mate with/not get eaten by. These poor blighters have enough to worry about without contending with a book or boot heading in their direction! You will often see them late at night, normally scurrying across the floor. I guess it is the movement that is one of the things that really bothers people; they are easily startled and bolt rather than retreat. This rapid movement can easily be misinterpreted as an attack. I have never heard of a house spider attacking anyone. They are a ridiculously timid species and their only thought is for flight, not fight.

Of course not everyone will be so tickled. House spiders (Tegenaria domestica to the press) unfortunately tick all of the boxes when it comes to people’s problems with spiders. They are large, hairy, prolific and fast. They are also completely harmless! I can understand a little the concern over Steatoda, they look a bit like the infamous Black Widow and can inflict a reasonably painful bite. They are also something that people have only recently started to notice thanks to a recent rapid expansion throughout most of the southern UK, though they don’t seem to have quite made it to the northern reaches. They are an introduced species and therefore their range is not quite nationwide just yet. Tegenaria, on the other hand have been here for much longer; you’ve all seen them and we should all know that they pose us no threat.

Beyond this it is certainly worth mentioning that the press are doing their best to spice things up a bit at least. Whether it’s the obsessed Daily Star, with their nearly constant arachnid-hating, or one of the other tabloids, spiders have once again started to make it back into the news in various ways, normally employing words such as “invading”, “rampaging”, “attacking”, or other such scary terms. Now, as it is that season again I shall bring my efforts to debunking each of these in turn, but this time around I am defending the house spider and the hobo spider that the press currently have their knickers in a twist over.

Let’s start with a few facts. Tegenaria is a genus of spider that is not invasive: in fact it has been introduced to much of the rest of the world from Europe! It consists of around 100 species, of which we enjoy just a few here in the UK. I’m not going to get too deeply involved in differentiating between the myriad subspecies as a: nomenclature and taxonomy of arachnids are headache-inducing at best and are also constantly changing, with Tegenaria currently under revision and some species seem destined for Erategina, so all these scientific names are soon to be redundant anyway. Suffice it to say it can be very difficult to tell spiders apart at times. So if many learned Arachnologists can sometimes struggle with these things – often a conclusive ID can only be obtained with microscopic inspection – how are we supposed to believe that a pest controller or nurse can make a positive identification, often without seeing the actual specimen?

Anyway, back to Tegenaria (or Erategina). Yes, they are the archetypical ‘creepy crawly spider’ that people tend to see as the days get colder. More often than not you will encounter a male out and about looking for a female to mate with/not get eaten by. These poor blighters have enough to worry about without contending with a book or boot heading in their direction! You will often see them late at night, normally scurrying across the floor. I guess it is the movement that is one of the things that really bothers people; they are easily startled and bolt rather than retreat. This rapid movement can easily be misinterpreted as an attack. I have never heard of a house spider attacking anyone. They are a ridiculously timid species and their only thought is for flight, not fight.

I mean, come on guys, this is a creature that cannot even negotiate a bathtub! How scary can they possibly be? It doesn’t help that they have a face that only a mother could love. They lack the adorable characteristics of peacock spiders (Maratus volans, for instance) or even the photogenic garden spiders (Araneus) and the proportions are those that will invoke the worst nightmares of the majority of common folk, being all gangly, hairy and lightning fast. However they are great at keeping the number of pests down and apart from the males you see on a quest for nookie, a very shy species that prefer to secrete themselves in extensive tunnel-like webs in corners of sheds. If you are to come across one it is more than likely to be in the bath as, as previously mentioned, they are incredibly inept at escaping the smooth sides of your average bathtub.

So with that introduction to the house spider, let’s have a look at a couple of the stories, shall we? To be clear, I will not be posting links to these tales of arachnid terror as I refuse to add to the advertising revenue of these scaremongering swine. It all started with headlines proclaiming Giant Spiders Set To Invade UK Homes This Autumn, Warn Experts, courtesy of the Mirror. And not to be outdone, the Daily Star gave usAttack Of The Giant Spiders: Scorching Summer Leaves Beasts Poised To Invade Britain.

Despite the fact that experts are warning no such thing – the headline is horribly out of context to the actual quotes given – this is something that happens every year. It gets cold. Spiders like it warm, spiders come inside. It’s nothing new and certainly not worthy of a headline, but I guess it is the kind of thing that will sell papers. I’m also unsure on how any arachnid can invade (surely one of the gutter press’ favourite verbs) Britain from within Britain: I was always of the impression that invasions came from outside of our sovereign lands. Maybe the editor of the Daily Star can help me out with this. I suspect my invitation will go unacknowledged, however.

One point I will concede is that the spiders do seem to be a bit bigger this year than in previous years. There are probably a few reasons for this: one is the weather of late, which has been ideal for the reproduction of the small flying insects that form the primary food source for the spiders. Of course, something else that may have resulted in a boom of prey insects is people indiscriminately slaughtering their predators around this time last year: you only have yourselves to blame, people! Anyway, it gets cold, spiders come in, you’ll see more spiders. Nothing to see here; move along.

After that non-event, they had another go at terrifying the public with the following beauty: They’re Invading! Terrified Couple Under Attack From Aggressive Venomous Spiders. Well, I suppose we should be thankful that they have started to make the correct distinction between venomous and poisonous at last! This aside, they’ve realised they need to give the story a bit of a twist to keep people interested, so we are introduced to a new arachnid terror: the Hobo spider, an “ultra-aggressive monster spider”. Mysteriously, none of the articles or ‘victims’ seem to be able to produce one, instead triumphantly brandishing dead male house spiders. Apparently, “Liam, dad of 3” has been bitten by one of these attack-minded killing machines and has a horrific wound that’s expected to take three months to heal – it looks a bit like a cigarette burn. His partner has encountered and killed around 30 of these monsters, although none of the dead spiders they portray seem to be particularly oversize.

Hobo spiders do exist. They are called Tegenaria agrestis, from the Latin for ‘field’ – their primary habitat. The effects of their bite are largely undocumented as there have been very few bites to go on. They are not aggressive and not monster. They are not native to England and I have never actually seen one in this country. All the pictures I have seen thus far purporting to be a ‘Hobo spider’ are a completely different species. Should Liam’s condition have developed from a spider bite I would think it was once again from a secondary infection rather than the venom itself. Describing to the spider to the intrigued journalist, Liam stated, “their bodies are pretty much normal size but it’s the legs – the front legs are the size of your hand.” The quote appeared immediately below a picture of a house spider barely bigger the one penny piece it was depicted with.

In a similar story involving a four-year-old child, the culprit is described as a 5” house spider even though the pictures attached to the article are of a garden spider (Araneus diadematus) and jumping spider (probably Salticus sp.) respectively. Five inches? The jumping spider maxes out at 5mm, so I am already taking this article with a big pinch of Salticus. (Sorry!). Secondly the picture of the rash on the poor child seems to follow an unusual and atypical distribution pattern, affecting the torso only. That’s a bit odd. Any rash caused by a bite would spread across the body, not be impeded by clothing. In fact, a rash like the one pictured could be something altogether viral or a reaction to a chemical on the skin, not envenomation from a bite. This could be an allergic reaction to a fabric softener for all we know!

According to the story, the staff at a walk-in medical centre – not even a hospital – “discovered an insect was to blame“ for the child’s condition and prescribed a course of tablets: a surprisingly well-informed and accurate diagnosis without bloodwork or consultation with an expert, even if we forget that spiders aren’t insects. I’m unsure what tablets you would prescribe for envenomation; however, I suspect that it may have been some kind of antihistamine, a drug family commonly used for allergic reactions. Regardless, it wasn’t considered serious enough for a trip to the hospital. There are endless things that could have caused this kind of reaction: the aforementioned chemical agent, a virus, flea bites, bed bug bites, dust mites bites (or at least the reaction to them) – but no, plainly the spider was to blame. I have never heard of a house spider biting anyone; it’s certainly possible, but every single one I have ever encountered, and we are talking hundreds here, has scarpered. So, I’m sorry, the evidence just doesn’t support the story in this instance. Notwithstanding the quality of these scaremongering reports – bad grammar is rife within – and the hilarious amount of ill-considered misinformation that they endlessly come up with, the only thing that I am horrified by is that this kind of reporting is not regulated in some way.

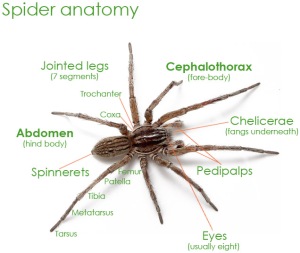

Now, I am under no impression that this is going to end any time soon; this has already been raging for some time, and it has started to reach a point where once again I have been compelled to say something about it. Spiders have few enough friends as it is: even members of their own (inherently cannibalistic) species want them dead. Let’s not add to their difficulties. Should you encounter one, just trap it under a glass, slide a bit of card underneath and pop it outside. If it’s a male, as it nearly always is – you can tell by their enlarged bulbous pedipalps or feelers – then it likely doesn’t have all that long to live anyway and it is really not interested in you in any event.

At the end of the day, a spider is not smart: they lack the brainpower for reasoned thought and every single encounter with another organism is probably best characterised thusly: “can I eat it or is it going to eat me?” The first response will result in a bite. Venom is used to kill prey; no other reason. The venom kills the prey, or at least renders it helpless, so that the spider can eat up all the juices at its leisure. If it is not something the spider can eat, then its primary reaction will be to flee. Spiders are not aggressive: nearly without exception they will not launch themselves at something they have no hope of eating, particularly not something that is several hundred or thousand times bigger than they, and waste precious venom in the process. Spiders can be defensive, reacting to provocation, but even then a bite will be a very last resort.

So don’t fear them. I don’t expect you to love them like I do, but maybe find a way to respect them. They are fascinating creatures – I will be following this up with a more generalised article in an attempt to persuade you – and it is unfortunate that they key into all our deepest primordial fears. Should you encounter a spider and be unsure of what type it is, don’t forget that there are several aids to identification. There is even a British Spider Identification group on Facebook that will gladly ID any specimen, preferably alive – it might even be me that comments.

So until next time, keep calm and carry on. After all, it’s only a spider.